In Appreciation: An African American Woman Lawyer on Dewey’s Mob-busting Team

By Kate O'Brien-Nicholson

21st March 2021

Originally published by Eilene Spear for The National Law Review on Saturday, 3/20/21

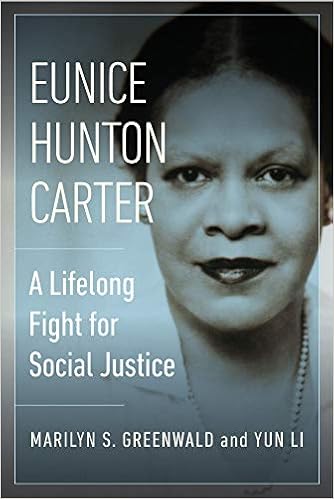

As the legal profession addresses issues of diversity, recruitment, and fairness, The National Law Review looks back to spotlight the role of an African American woman attorney on Thomas Dewey’s mob-busting prosecution team during the Great Depression. We interviewed Marilyn Greenwald, professor emerita of journalism at Ohio University, about Eunice Hunton Carter. Carter helped convict Charles “Lucky” Luciano in 1936 and later served as a legal advisor to the early United Nations. Professor Greenwald and Yun Li are co-authors of a book on Carter that will be released in April: Eunice Hunton Carter, A Lifelong Fight for Social Justice (Fordham University Press). Li earned a Masters degree in journalism from Ohio University in 2016 and is now a reporter at CNBC.

This fascinating look at history explains the role of a legal pioneer and also deals with litigation topics as timely as today’s headlines: jury selection, the power of the state, preparation of witnesses, and the role of the press.

NLR: The legal profession, media, and other institutions are focused on spotlighting forgotten figures from history, particularly women of color. How did you learn about/discover the African American woman lawyer on Thomas Dewey’s mob-busting prosecution team?

Answer: We learned about Eunice Hunton Carter during a visit four years ago to the Mob Museum in Las Vegas, a non-profit museum dedicated to the history of organized crime. The museum features an exhibit about the sensational mob trial of Lucky Luciano during the summer 1936. On the walls are individual photos of Special Prosecutor Thomas E. Dewey and his team of 20 assistant prosecutors, whom the press had labeled the best attorneys in the city. All were men, and all were white – except for one black woman. We knew at the time that there must be an interesting story behind her appointment during an era of stifling racism and sexism, and at a time when very few attorneys were women.

NLR: June 7, 2021 marks the 85th anniversary of the Lucky Luciano conviction. What stands out about this case, and the role of Ms. Carter?

Answer: Carter established the crucial link between prostitution and mob activity — a connection that had been unrecognized by law enforcement officials, and one that ultimately clinched the case. Law enforcement officials in New York City and around the country had been unable to prosecute members of organized crime for actual criminal activity. In Chicago, Al Capone was prosecuted for tax fraud; other mobsters slipped through the legal system entirely. So prosecutors had their work cut out for them. Before she was appointed to the legal team, Carter – the first black female assistant prosecutor in New York – had been working in Manhattan’s Women’s Court, where much of her job consisted of prosecuting prostitutes. After Dewey named her to the team, she remembered that many of the penniless prostitutes she had prosecuted employed high-priced attorneys and bail bondsmen. She theorized that the financial help may have been coming from the mob.

Dewey at first rejected her theory; he didn’t believe it, and thought it would be bad public relations for the team to imply that poor prostitutes were somehow involved with mob activities. After more research by Carter and another member of the team, the theory was borne out. Carter was also instrumental in extracting evidence from the prostitutes and prepping them for their testimony. At first, the women were so intimidated by other tough investigators on Dewey’s team that they wouldn’t speak up. Carter ultimately earned their trust and had them open up so that they would serve as credible witnesses. The testimony of the prostitutes – and what they witnessed – was breathtaking and emotional.

NLR: Dewey and Carter formed a lifelong friendship and professional alliance after the mob trial, even though they were very different personally. How did these differences help the prosecution?

Answer: Carter had a low-key personality and a quiet demeanor. Dewey, who was once a professional singer, was a showman who loved the spotlight.

Carter’s forte was conducting dogged research, often perusing thousands of documents in solitary offices and libraries for weeks at a time. Dewey used his charismatic personality to get information from people and subtly – sometimes obviously—manipulate people and institutions. Dewey, the consummate public-relations man, realized that the legal team could not work effectively under the continual scrutiny of the press and the public. So he met with top editors and publishers to work out a deal – if the newspapers of the era would lighten or eliminate their coverage of the investigation, Dewey would talk to reporters when the probe was completed. The editors agreed, and the actual year-long investigation and the prosecution’s methods got very little coverage in the New York newspapers.

NLR: Dewey was a charismatic prosecutor and he of course won the Luciano case. But wasn’t the team accused of using some questionable tactics?

Answer: Lucky Luciano was convicted of more than 60 counts of compulsory prostitution and sentenced to 30-to-50 years in prison. It marked the first time a New York mob boss was found guilty of a significant felony. Thomas Dewey instantly rose to fame as the nation’s top mob buster.

After the trial, some labor officials and civil libertarians questioned some of his tactics during the investigation. Dewey arrested 100 women in secret round-ups and left them behind bars at the New York House of Detention in Greenwich Village as material witnesses. All the prostitutes were kept in jail while Dewey’s lawyers interviewed them day and night, and sometimes threatened them with prison time if they did not agree to link Luciano to the vice ring. This practice was under scrutiny on cross-examination during the trial. After the trial, some of the prostitutes recanted their testimony, but the verdict was maintained, and a retrial was denied.

Other questionable methods revolved around jury selection and wiretaps. Judge Philip McCook approved Dewey’s request for what was called a “blue-ribbon” jury – a jury made up of middle- and upper-class people, all of whom had served previously on juries. The Luciano jury consisted of 14 white men, many of whom were business executives. Dewey’s team even approached the president of Goldman Sachs to be a juror. All of them had also read about the case in the newspapers, which at the time were overwhelmingly supportive of Dewey, painting Luciano as the nation’s most dangerous and brutal crime lord. Later, research indicated that in more than three-fourths of criminal cases studied, “blue-ribbon” juries voted to convict. The year after the trial, the New York state senate attempted to abolish such juries but they were not ruled unconstitutional in New York until 1965.

Without a court order, Dewey authorized full-scale wiretaps and the tailing of some of the key bookers, which uncovered the inner workings of the prostitution ring. The wiretaps confirmed the fact that many prostitutes had used the same lawyers employed by the mob to get them out of trouble. The liberal use of wiretaps was widely criticized in the aftermath of the trial. The New York state senate also attempted to limit the use of wiretaps shortly after the trial when some labor organizations and civil libertarian groups claimed law enforcement abused their use. These groups argued that evidence gathered from wire taps should be held to the higher standards followed in federal courts. Due in part to a politicized atmosphere – with Republicans including Dewey opposing the proposal and Democrats supporting it – the measure was defeated.

Interestingly, these questionable methods were not brought to light by any of the reporters who covered the case – or, if they were, their controversial use did not appear in published stories.

NLR: How did Thomas Dewey come to know about Carter and her work?

Answer: In some ways, Dewey was ahead of his time when he hired the team to investigate the mob. For instance, he hired Jewish lawyers on his team at a time when some law firms would not hire Jews. He always maintained that he hired the best people for the job regardless of their race, ethnicity or religion.

In the case of Carter, she entered Dewey’s radar after a brutal race riot in Harlem in 1935 that led to scores of injuries and the arrest of 50. Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia immediately appointed a bi-racial, eleven-person panel to investigate the possible causes of the riot. Carter, who was then a social worker in Harlem, was named as the group’s secretary, assigned to collect tips and evidence and organize the final report. The group concluded that the ultimate cause of the riot was economic inequality, and it marked the first time that black residents spoke about the toll poor housing, unequal education and inferior medical care took on their neighborhoods. Her work – which ultimately resulted in the passing of seven bills in the state legislature – was widely admired, leading to praise from LaGuardia himself. Shortly thereafter, Dewey named her to his team.

NLR: How did Carter manage to succeed as an attorney and prosecutor in a profession that was almost exclusively white and male?

When Carter graduated from Fordham Law School in 1932, there were few white women and even fewer black women in the profession. In 1920, there were about 1,500 female lawyers in the United States and only four were black, according to Ebony magazine. By 1947, there were 6,615 women lawyers in this country, 83 of whom were black, compared to 174,550 male attorneys.

Carter succeeded in part because she was adept at networking and working to cultivate alliances with other attorneys and with other women who were interested in social justice and civil rights causes. She had always been a member of several attorney organizations, and she was extremely active in the clubwomen’s movement, a reform movement formed in the 19th century devoted to community service and designed to improve the lives of women and families through the promotion of education, health, and women’s suffrage. For decades, Carter was an officer or a board member of the influential National Council of Negro Women, and she served as its legal advisor for many years.

NLR: Besides the Luciano case, how else did Eunice Hunton Carter stand out?

Answer: Carter and Dewey became lifelong friends and associates; after the Luciano case, he was voted New York County prosecutor, and he named Carter head of the office’s Special Sessions bureau, which handled 14,000 misdemeanor cases a year. She worked there nine years before returning to private practice and becoming more active in civic and social-justice causes. A lifelong Republican, she also campaigned for Dewey during his bids for New York governor and U.S. President. Shortly after she left the prosecutor’s office and re-entered private practice, Carter became a legal adviser to the United Nations shortly after its founding in 1945, working with Mary McLeod Bethune and other national educators and reformers.